The DSA Newsletter #6

This is your DSA update for May to September 2024. It covers pioneering examples of private enforcement of the DSA, explains what is happening in the world of out-of-court dispute settlement (ODS) bodies, and the case of Mr Durov (Telegram), updates on the DSA enforcement actions, the new Commissioner responsible for the DSA, and on the ongoing work on the guidance for the protection of minors, and, finally, it brings big personal news on my new book, and online courses.

1. Big personal news

Let me start with my personal news first. Principles of the Digital Services Act (OUP, 2024) has finally landed in your bookshops. You can buy it from OUP or Amazon. Moreover, I have also launched two new online courses on the DSA:

- The DSA Mini Course — a free course that explains the fundamentals in under 45 minutes.

- The DSA Specialist Masterclass — a true comprehensive masterclass that includes more than 12 hours of video lectures of me explaining all parts of the DSA, and offering many hypotheticals, quizzes, additional resources, tests and a certificate.

The DSA Mini Course is ideal for anyone who wants to become familiar with the law. It is completely free. The DSA Specialist Masterclass is for everyone who wants to become an expert on the DSA. The Masterclass incorporates my teaching concept, enriched by two years of training experience of more than 300 professionals from regulators, companies, NGOs, and law firms. I explain why built this unique Masterclass in this video. In a nutshell: we lack professionals who understand the law; there is a huge demand for them but few options to get educated. Well, now there is. Go and try it out.

2. Private enforcement of the DSA

I have been preaching from the early days that the DSA is a hybrid enforcement model. Unlike the UK’s OSA, it is much more open to private enforcement. Not all obligations can be privately enforced in my view (e.g., Articles 34-35 cannot), but many can be and will be. I am glad that we see the first plaintiffs proving my point in courts of the Member States.

Mr Mekić recently secured a win in a dispute relying on the DSA in the Netherlands (see here). His story is about shadow-banning by X, probably triggered by his criticism of the EU CSAM regulation. X’s tools wrongly moderated his account and stopped showing it in the search box. My understanding is that Mr Mekić won on contractual and DSA grounds. Plus, he also won a separate case on data protection grounds. Paddy Leerssen has a nice blog post explaining the context here.

Another successful example is the German case of collective redress against Temu. Wettbewerbszentrale is a German Center for Enforcement of Unfair Competition Law. The Center has been using the collective redress in the unfair competition law to enforce the fairness of competition for more than 100 years (see more context). The Center initiated cases in German courts against Temu and Etsy, in both cases due to violations of Article 30 of the DSA which requires platforms to collect information about their sellers. Temu now decided to settle and signed a contractual undertaking to implement Article 30 DSA properly. The Center’s case against Etsy is still pending. Interestingly, the Center also started a proceeding against an entity that misled the public about its status as a Trusted Flagger under the DSA. The entity lacked any DSA certification.

Private enforcement by consumers (as contractual claims) and collective redress (as tortious claims) by associations of traders or consumers are both very likely in practice. Among other things, they benefit from the rules of international private law that allow the plaintiffs to bring actions in their home jurisdictions against EU-established platforms, provided that the activities are targeting that home jurisdiction (Article 17(c) Brussels Recast [consumer contracts]), or damage has occurred there (Article 7(2) Brussels Recast [tort and related actions]). While for tortious claims the case law insists on their territorial limitation, the issue with injunctive relief is that even if you have to comply with the DSA, e.g., Article 30, for one jurisdiction, in many cases, you effectively likely comply for others too. Unlike these two types of claims, contract-based claims of business users, on the other hand, can struggle with jurisdiction. A good example of this is the recent case of HateAid, an NGO incorporated as a limited liability company, which was rejected by the Regional Court of Berlin due to the lack of jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction issue is key because private enforcement is the only way how plaintiffs can overcome Europe’s ‘one-stop shop system’ that allocates the competence for public enforcement with Digital Services Coordinators (DSCs) of establishment and the European Commission (for VLOPs). For the majority of VLOPs in the EU, this is Ireland. Thus, the flexibility of the rules of private international law on jurisdiction determines the extent to which parts of the DSA can be enforced in the country of destination. If you are a student reading this, the issue makes for a terrific research problem.

3. The certification of ODS bodies is in full swing

One of the most experimental aspects of the DSA is undoubtedly Article 21 that grants the users a right to file an external appeal to an out-of-court dispute settlement (ODS) body. The decisions of these bodies are not binding but platforms must arguably explain why they do not implement them. Many aspects of the system are not properly solved by the DSA. The financing is subject to framework rules that allow various fee structures. As many of you know, I have been advocating for ODS-like systems for years before the DSA. Together with a co-author, we provided evidence for the potential benefits of the system in an experimental empirical study. However, abstract experiments need calibration on the ground to work. The DSCs, with their first certification decisions, and ODS bodies, with their early practice, are now doing that calibration.

There is a lot to be said about the system, and you can certainly expect that I continue to research and write in this area. I sincerely hope that the system can improve content moderation practices. At this point, I want to make several early observations about what is happening on the ground.

First, following the adoption of the DSA, there was a big concern that no one might actually seek certification as an ODS body. I am now aware of 10 organisations that are either certified (3), their application is pending, or are preparing for certification. This shows that there is a lot of interest in the system. At the time of writing, the following three bodies were certified: User Rights (Germany), ADROIT (Malta), and OPDR Council (Hungary). All of them are already processing the first cases.

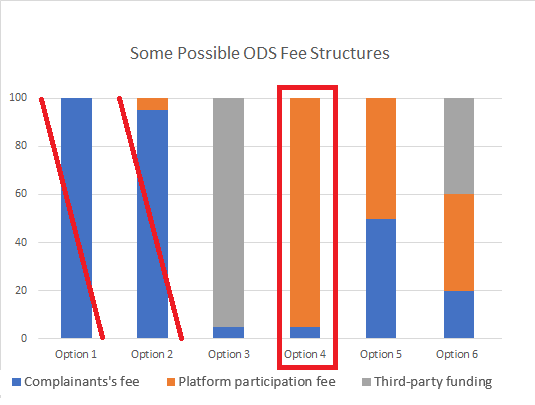

Second, after the adoption of the DSA, we could see different predictions as to the future financing models. The DSA only sets a framework for financing. The basic rules are: (1) ODS bodies can only charge fees to platforms and complainants (users or notifiers); (2) complainants’ fees must be ‘nominal’; (3) if a platform loses, it must compensate complainants’ fees and reasonable cost (fee shifting, see Article 21(5)); (4) if the complainant loses, it does not have to compensate a platform, unless it ‘manifestly acted in bad faith’.

I changed my views on what is possible under the system over time. However, eventually, I prefer fee structures where users pay more than symbolic, yet still nominal fees, and the remainder is paid by the platform or an independent funder, such as the state or philanthropies. The initial certifications show that this is neither the preferred (by ODS bodies) nor the required model (by regulators). Nominal takes the meaning of symbolic instead of (very) small compared to the actual value/cost (see the dictionary). In the picture below, you can see several possible and prohibited fee structures. Of course, in reality, the options exist on a spectrum between the above options, so consider them only as models. Some might consider even Option 5 as prohibited.

The model of zero or symbolic nominal fees (Option 4) is clearly preferred by ODS bodies. Platforms are asked to pay hundreds of euros per case (e.g., User-Rights charges 200-700 euros per case [p. 3]). Complainants can file their cases free of charge.

I think the choice is legitimate and understandable if you want to educate the public about the possibility of such redress. After all, we cannot simply assume that the demand for this service exists. No one knows how this will work in practice yet.

However, the choice of Option 4 has consequences for the DSCs who will have to monitor more closely the upcoming practice. The in-built incentives differ substantially across the fee structures. While Options 5 and 6 (or similar options that get close) still preserve some link between the aggregate ODS costs and the success rate of platforms and therefore reward good internal content moderation, under Options 3 and 4, platforms are not able to influence the amount of ODS fees they pay by being right. Their only available strategy is to try to convince future complainants (notifiers and content creators) not to complain due to the merit of their decisions.

On the other hand, Options 3 and 4 remove the demand-side constraints because the service is free, or provided for a very low price. This makes it much more affordable and accessible. We have such models in some areas, such as flight compensation ADR. But those are much more narrow disputes than ones arising from content moderation.

For content moderation, the abusive behaviour of complainants is a given. And if the fee for them is non-existent, or symbolic, the only risk for complainants is having to pay platforms’ fees or costs for manifestly bad faith behaviour, as they do not have to worry about losing their own fees. However, such a threat is not credible if complainants pay nothing upfront as platforms are unlikely to recover anything on their own. Thus, the first challenge is curbing the abusive behaviour of complainants. Another challenge lies in the incentive structure for the ODS bodies that are incentivised by volume: more cases, means more fees. There are some in-built checks against this as well, such as de-certification, strategic rejection by platforms, or potential loss of reputation which can impact the demand, but these safeguards must be operationalised to work properly.

In other words, a lot of work is ahead of us all.

4. Guidance on Article 28

Over the summer, the Commission published a consultation asking for evidence for its future guidance on Article 28 which concerns the protection of minors. This will be by far the most consequential guidance that the Board and Commission will write in the first years.

Article 28 DSA, unlike anything that EC does with VLOPs, applies to thousands of online platforms operated by mid-sized companies (or mid-sized holding companies). The deadline is 30/09/2024. Four days before the deadline, there were only 53 submissions online, maybe one-third serious, from regulators (e.g., French and Slovak DSCs), NGOs and very few companies. Obviously, many might submit their briefs at the last minute. Even if the Commission consults again after the draft is released, this is the only chance to submit evidence or policy positions before the framework is already prepared.

The guidance will have an impact on how services ranging from adult sites, social media, and dating apps, to online marketplaces, discussion forums, or food deliveries, interact with children and the general public. The issues like age verification and recommender systems design will be clearly on the agenda.

5. New European Commissioner for the DSA

By now, you have surely heard that Mr Breton stepped down and will be soon likely replaced by Ms Virkkunen from Finland as the new Commissioner responsible for the DSA. While Mr Breton might have raised the profile of the DSA as a regulation, he also seriously politicised the public perception of the DSA, especially through his exchanges with Musk and letters that sometimes misrepresented the law.

Ms Virkkunen’s appointment is thus undoubtedly good news for the DSA enforcement. She has worked on several digital files in the European Parliament, including the Pegagus spyware investigation. The mission letter tasks her to enforce the DSA and develop responses to addictive design, influencers, online bullying, dark patterns, and e-commerce platforms. These are thus areas where we can expect further upgrades (or downgrades) of the DSA.

The addictive design discussions are very likely to be part of the debate about Article 28 guidance as the design of recommender systems and various gamification scenarios clearly fall in its scope. It is thus possible that some of the work on the guidance could also end up influencing this future policy file on a new piece of EU law. In other words, there are many reasons to submit your views to the open consultation.

6. Mr Durov’s [Telegram] case

Mr Durov’s case (see Tech Policy’s tracker) is fairly interesting in highlighting one issue about the EU legal landscape. After Mr Durov was arrested, many people wondered if this could have anything to do with the DSA. Hardly. The DSA does not include any criminal penalties and does not (unlike the UK’s OSA) link companies’ responsibility with that of their CEOs. Mr Durov’s case shows nicely why Chapter 2 of the DSA is still very important. According to numerous reports (see e.g., NYT reports), Mr Durov for years rejected to implement orders received from authorities around the world, including European ones. The only thing that protects hosting providers like Telegram from imposing criminal liability for aiding and abetting is one of the European liability exemptions (now in Article 6 of the DSA).

However, the liability exemption is conditional upon acting on acquired knowledge of manifest illegality. Thus, ignoring the orders is the surest way how to lose it.

French prosecutors therefore only need to show orders that were ignored and Article 6 does not protect Telegram or Mr Durov anymore. And once that provision fails to apply, the DSA is the least of Mr Durov’s concerns. At that point, French or any other national criminal law can impose criminal liability, including on the CEOs of the platform, for ignoring orders.

The due diligence obligations in the DSA in that sense are a law for good citizens who should only strive to do better. In contrast, those who systemically and on purpose lose liability exemptions, have much bigger issues to worry about anyway. They can face civil and criminal liability, including for their CEOs. Therefore the best analogy for allegations against Mr Durov is not the infamous Mr Somm’s case, as I have seen some people argue, but Mr Sunde’s case. Let me explain.

Mr Somm, was the CEO of the German branch of Compuserve, a discussion forum popular in 90ties. Before the European Union adopted the liability exemptions, he was initially held criminally liable by German courts for hosting CSAM content on its service. Despite the fact that Compuserve always acted upon notifications, he was found criminally liable for not knowing.

Mr Sunde, in contrast, was one of the founders of the Pirate Bay who was also held criminally liable by the Swedish Supreme Court for aiding and abetting copyright infringement. The liability exemptions were already in place. However, they did not apply because The Pirate Bay had full knowledge of specific infringing acts on its service. He only decided to ignore them. Mr Somm, in contrast, would today count as a good citizen who only should improve the service’s systems and processes under the DSA.

In short, new rules in the DSA are mostly for good citizens who can do better. Bad guys have other harsher laws to worry about, as they can face the full power of the legal system, including criminal law. They are left unprotected by the liability exemptions that are otherwise offered by the DSA to providers. And while losing liability exemptions does not imply liability, to be sure, ignoring valid legal orders is a different league. Chapter 2 of the DSA is thus usually a ticket to a better society. It is not too dissimilar to how our legal response is different for CEOs of banks intentionally assisting criminals laundering money from crimes through their financial services, and those CEOs whose banks only fail to be diligent.

7. Enforcement of the DSA

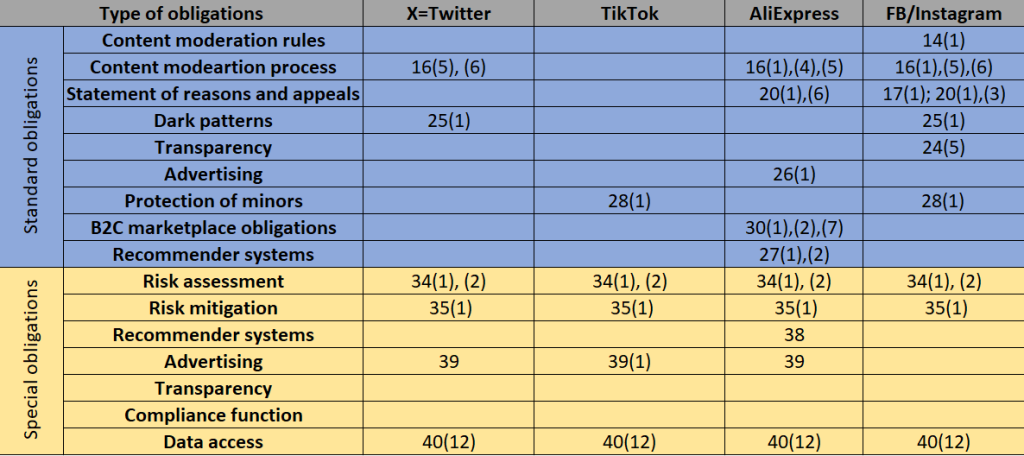

The Commission has only expanded its investigation into Meta and otherwise not opened new investigations since the last newsletter. Below is the updated table (with Meta’s new Article 28 (minors) related investigation).

The Commission did send a couple of new RFIs to companies, including Meta (regarding Crowdtangle), Amazon (transparency of recommender systems, and risk assessments), Shein and Temu (on several issues), Pornhub, Xvideos, Stripchat (on illegal content and minors), X (content moderation resources). The Commission also designated Temu (an online marketplace) and XNXX (an adult site) as two new VLOPs.

The key wins for the Commission are TikTok’s acceptance of commitments over TikTok Light and LinkedIn’s announcement to disable some advertising functionalities. TikTok’s acceptance of commitments is quite interesting. Given that the Commission’s win was mostly procedural, i.e. TikTok apparently did not carry out a specific risk assessment for a new feature with a critical impact, it is surprising that TikTok would commit to never launching the Light program in the EU.

The Commission also compelled Microsoft to hand over more information about how generative AI is integrated into Bing. It seems to have followed the same playbook as with TikTok because the Commission is likely asking for the disclosure of a separate risk assessment over the launch of a new feature that can have a critical impact (see Article 34). Given that nothing has happened since May, unlike in TikTok’s case, it seems that Microsoft had something ready to satisfy the requirement.

The first case that is likely to proceed to the stage of fines concerns Musk’s X. In July, the Commission sent X its preliminary findings. It singled out dark patterns (Article 25), advertising transparency (Article ) and data access for researchers (Article 40(12)). Here is what the PR states:

First [dark patterns: Article 25], X designs and operates its interface for the “verified accounts” with the “Blue checkmark” in a way that does not correspond to industry practice and deceives users. Since anyone can subscribe to obtain such a “verified” status, it negatively affects users’ ability to make free and informed decisions about the authenticity of the accounts and the content they interact with. There is evidence of motivated malicious actors abusing the “verified account” to deceive users.

Second [advertising transparency: Article 39], X does not comply with the required transparency on advertising, as it does not provide a searchable and reliable advertisement repository, but instead put in place design features and access barriers that make the repository unfit for its transparency purpose towards users. In particular, the design does not allow for the required supervision and research into emerging risks brought about by the distribution of advertising online.

Third [data access: Article 40(12)], X fails to provide access to its public data to researchers in line with the conditions set out in the DSA. In particular, X prohibits eligible researchers from independently accessing its public data, such as by scraping, as stated in its terms of service. In addition, X’s process to grant eligible researchers access to its application programming interface (API) appears to dissuade researchers from carrying out their research projects or leave them with no other choice than to pay disproportionally high fees.

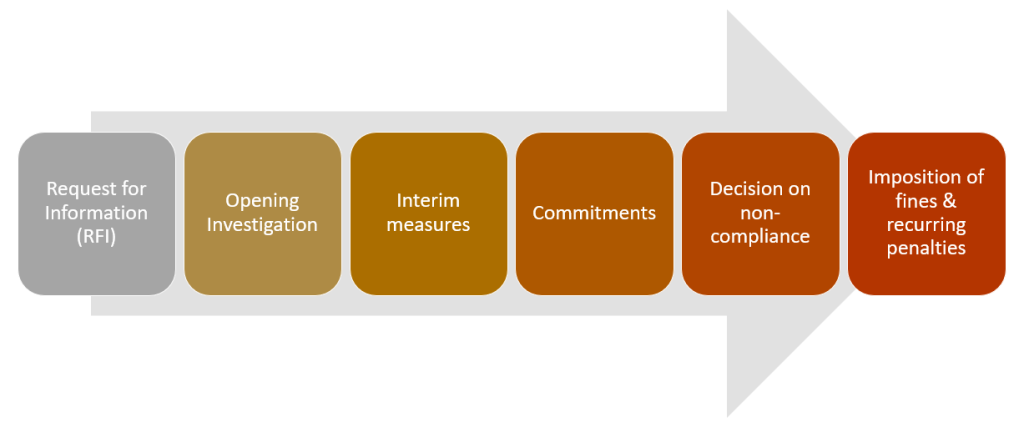

The technicalities were overshadowed by the Musk/Breton exchanges. Musk claimed that the EU offered it a secret deal to censor its platform. Well, super secret, it turns out. Under the DSA, the enforcement train looks something like this:

That ‘secret deal’ was the offer of commitments, a tool used in competition law for years. Musk could publish his commitments. Moreover, commitments did not relate to content at all. It was about Musk’s “speech-absolutist practices”, like not sharing data with researchers (or suing them), and failing to implement transparency. The Commission’s pick of Articles 39 and 40 is very strong, and X is clearly only playing a delay tactic, nothing else.

Based on the fact that other points from the investigation did not progress this far (e.g., Community Notes claims), shows that the Commission is conscious of the evidentiary limits for risk management. While X is a good poster child for a first case, building an Article 35 case won’t be cheap or quick. I discuss this extensively in my book.

The dark patterns claim will be more interesting to watch, as the carve-out in Article 25(2) has an uncertain scope. The new Commission might even tinker with it if they legislate on dark patterns.

Finally, Irish CNaM now sent the first batch of its RFIs to platforms to understand their compliance with Articles 12 (user contact points) and 16 (illegal content). They have prepared a helpful fact sheet here. The action concerns (1) VLOPs: TikTok, YouTube, X, Pinterest, LinkedIn, Temu, Meta and Shein, and (2) non-VLOPs: Dropbox, Etsy, Hostelworld and Tumblr.

8. Miscellaneous

There is a lot of great work that has been published since May. But to properly review it, I need more time. However, here are some tidbits of news or papers that caught my eye:

- Approximately 20% of users would opt out of using personalized recommender systems, according to a study by Starke and others.

- A 2024 study by Bright and others concludes that: “Approximately 26% of respondents said that they had had a piece of content deleted by a social media platform at least once, with around 16% saying it had happened more than once. This indicates the widespread nature of content moderation. Of those who had had content removed, approximately 48% launched a subsequent appeal process, and 30% of these people received what they regarded as a satisfactory response.”

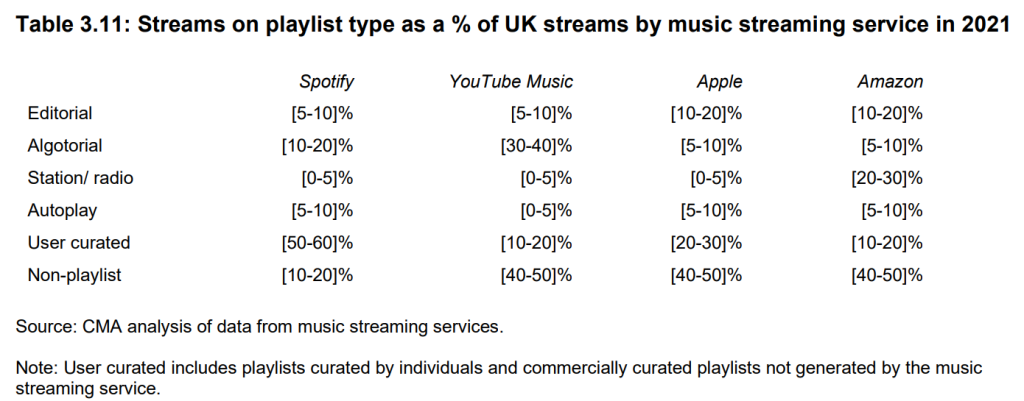

- The UK Music and Streaming study from 2022 includes interesting stats about the impact of user-generated playlists on the listening habits of users. This can be relevant for Spotify’s DSA classification.

- Hungary seeks invalidation of European Media Freedom Act before the CJEU.

- Agne Kaarlep (Tremau) on risk assessments.

- Researchers call for access to conduct experimental evaluations of VLOPs.

- JD Vance says that NATO military support should be conditional upon the EU respecting the US freedom of speech values.

- My book launch takes place at LSE on 11.11, you can pre-register here. The proper registration opens soon.