Is There Any Union Wide Secondary Liability?

‘Is There Any Union-wide Secondary Liability?’

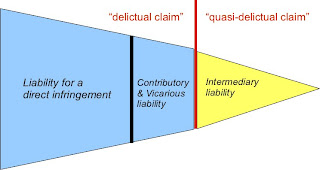

Firstly, let me explain what I mean when I use the term ‘secondary liability’. I mean liability of any person different from the direct infringer, who has to bear the weight of any kind of non-contractual claims. To outline the different types of liability, I am using categories of American law, plus one purely European category. In my understanding here, the European secondary liability includes:

a) vicarious liability, which is a liability instead of somebody (typically liability of an employer for acts of his employees);

b) contributory liability, which is a liability together with somebody – i.e. liability based upon acts or conduct that induce, contribute to or further an infringement (typically liability of an aidor or an abettor);

c) intermediary liability, which is a liability for purely enabling infringements, without being liable within contributory liability or vicarious liability scheme (typical example would be liability of Internet access provider to block certain website);

In the picture, it would look like this:

Yes, the intermediary liability is something I just made up here to reflect the art. 8(3) of Information Society Directive and art. 11 of Enforcement Directive, so please bear with me for a while. The common view in European Union is that although we have certain absolute rights harmonized (even unified), the secondary liability standards are up to member state’s law. So for instance, if the absolute right of the author to distribute his work is infringed, the Union law will determine who is the direct infringer, but the member state law will have to determine secondary liability. So for instance, aiding the infringement of direct infringer would have to be determined under e.g. French or German law. Theoretically, France and Germany could have different standards for what triggers the secondary liability and thus applicable law could lead to different result about who is secondary liable. For instance, the French law could regard aiding to be infringing if its at least negligent contribution to the direct infringement and German law could require aiding to be intentional contribution of such a kind. The secondary liability thus even in the field of copyright and industrial rights is seen as merely ‘local issue’, most of the time based on the local general tort law.

Next common view is that intermediary liability (based on art. 8(3) InfoSoc, art. 11 IPRED), as a type of secondary liability, does not lay down substantial standards, and thus its upon the member state to determine when the intermediary liability is being triggered. The intermediary liability is only liability to cease and desist, and to remove the infringement. Therefore again, two countries could set up different requirements for intermediary liability (and EU countries did). The requirements of art. 3 IPRED are seen only as limitations of such a liability and not as the determinants of its scope. In other words, according to common view, countries are in compliance with the directive as far as they provide for some claims and do not provide them against said set of requirements. The common view is based on recital 23 of IPRED.

(23) Without prejudice to any other measures, procedures and remedies available, rightsholders should have the possibility of applying for an injunction against an intermediary whose services are being used by a third party to infringe the rightsholder’s industrial property right. The conditions and procedures relating to such injunctions should be left to the national law of the Member States. As far as infringements of copyright and related rights are concerned, a comprehensive level of harmonisation is already provided for in Directive 2001/29/EC. Article 8(3) of Directive 2001/29/EC should therefore not be affected by this Directive.

So it is believed that the system of secondary liability is currently build in the following way:

a) primary liability (liability of direct infringers) – in some IPR fields Union law (e.g. copyright, trade marks).

b) vicarious liability – law of the member states;

c) contributory liability – law of the member states;

d) intermediary liability – limits in Union law, but requirements in the law of the member states;

Now, first I want to point your attention to quite recent case Donner C‑5/11, which concerned the criminal proceedings against the transporter for aiding and abetting the unlawful distribution of a work protected by copyright law in Germany, but not in Italy. In course of reasoning, the CJEU inter alia said following:

24 The notion of ‘distribution to the public … by sale’ in Article 4(1) of Directive 2001/29 must accordingly, as observed by the Advocate General in points 44 to 46 and 53 of his Opinion, be construed as having the same meaning as the expression ‘making available to the public … through sale’ in Article 6(1) of the CT.

25 As observed by the Advocate General in point 51 of his Opinion, the content of the notion of ‘distribution’ under Article 4(1) of Directive 2001/29, must moreover be given an independent interpretation under European Union law, which cannot be contingent on the legislation applicable to transactions in which a distribution takes place.

26 It must be observed that the distribution to the public is characterised by a series of acts going, at the very least, from the conclusion of a contract of sale to the performance thereof by delivery to a member of the public. Thus, in the context of a cross-border sale, acts giving rise to a ‘distribution to the public’ under Article 4(1) of Directive 2001/29 may take place in a number of Member States. In such a context, such a transaction may infringe on the exclusive right to authorise or prohibit any forms of distribution to the public in a number of Member States.

27 A trader in such circumstances bears responsibility for any act carried out by him or on his behalf giving rise to a ‘distribution to the public’ in a Member State where the goods distributed are protected by copyright. Any such act carried out by a third party may also be attributed to him, where he specifically targeted the public of the State of destination and must have been aware of the actions of that third party.

28 In circumstances such as those at issue in the main proceedings, where the delivery to a member of the public in another Member State is not effected by or on behalf of the trader in question, it is therefore for the national courts to assess, on a case-by-case basis, whether there is evidence supporting a conclusion that that trader, first, did actually target members of the public residing in the Member State where an operation giving rise to a ‘distribution to the public’ under Article 4(1) of Directive 2001/29 was carried out and, second, whether he must have been aware of the actions of the third party in question.

[..]

36 The application of provisions such as those at issue in the main proceedings may be considered necessary to protect the specific subject-matter of the copyright, which confers inter alia the exclusive right of exploitation. The restriction on the free movement of goods resulting therefrom is accordingly justified and proportionate to the objective pursued, in circumstances such as those of the main proceedings where the accused intentionally, or at the very least knowingly, engaged in operations giving rise to the distribution of protected works to the public on the territory of a Member State in which the copyright enjoyed full protection, thereby infringing on the exclusive right of the copyright proprietor.

a) “A trader in such circumstances bears responsibility for any act carried out by him .. “ (refers to direct infringement);

b) ” .. or on his behalf giving rise to a ‘distribution to the public’ in a Member State where the goods distributed are protected by copyright” (refers to vicarious liability);

c) “Any such act carried out by a third party may also be attributed to him, where he specifically targeted the public of the State of destination and must have been aware of the actions of that third party.“ (refers to contributory liability);

Its not easy to deny that this paragraph is a part of the interpretation of the autononoums concept of the ‘distribution right’ because nobody would probably doubt that the other part about ‘targeted the public of the State of destination’ is part of such autonomous test under the Union law. I am really wondering what this means, not only for the other economic copyright rights such as ‘the communication to the public’, but also for the trade mark law for instance. Is it now up to the CJEU to decide whether the act of contributing to the infringement triggers secondary liability? Plus, for countries where for instance contributory liability is dependent on the intent to aid the infringement, does this mean that they have to lower the standard for the copyright law, or at least infringement of the right to distribution? What about joint and several liability of direct infringer and of contributory infringer?

All these questions might seem to be preliminary, but who remembers what happened with one paragraph of Infopaq C-5/08 that was later repeated in next five cases, and possibly rewrote the European copyright term of a ‘work’, may know why I am asking these questions.

The second question to be asked is what about intermediary liability? Is the common view correct? Several months ago I read a comment of Prof. Nordemann about L’Oreal v. eBay C-324/09. He asks whether the old German concept of Störerhaftung that was deemed enough to implement art. 11 IPRED and art. 8(3) InfoSoc, is still compliant with the Union law (GRUR 2011, Nordemann, Haftung von Providern im Urheberrecht. Der aktuelle Stand nach dem EuGH-Urteil – L’Oréal/eBay). His reason for asking this question is because the German concept requires certain breach of the duty of care („Verletzung von Prüfpflichten”). Prof. Nordemann points to paragraph 127 of said decision and following part:

127 It involves determining whether that provision requires the Member States to ensure that the operator of an online marketplace may, regardless of any liability of its own in relation to the facts at issue („unabhängig von seiner etwaigen eigenen Verantwortlichkeit in den streitigen Sachverhalten”), be ordered to take, in addition to measures aimed at bringing to an end infringements of intellectual property rights brought about by users of its services, measures aimed at preventing further infringements of that kind.

128 For the purpose of determining whether the injunctions referred to in the third sentence of Article 11 of Directive 2004/48 also have as their object the prevention of further infringements, it should first be stated that the use of the word ‘injunction’ in the third sentence of Article 11 differs considerably from the use, in the first sentence thereof, of the words ‘injunction aimed at prohibiting the continuation of the infringement’, the latter describing injunctions which may be obtained against infringers of an intellectual property right.

129 As the Polish Government in particular observed, that difference can be explained by the fact that an injunction against an infringer entails, logically, preventing that person from continuing the infringement, whilst the situation of the service provider by means of which the infringement is committed is more complex and lends itself to other kinds of injunctions.

130 For that reason, an ‘injunction’ as referred to in the third sentence of Article 11 of Directive 2004/48 cannot be equated with an ‘injunction aimed at prohibiting the continuation of the infringement’ as referred to in the first sentence of Article 11.

Article 11 IPRED [Injunctions]

Member States shall ensure that, where a judicial decision is taken finding an infringement of an intellectual property right, the judicial authorities may issue against the infringer an injunction aimed at prohibiting the continuation of the infringement. Where provided for by national law, non-compliance with an injunction shall, where appropriate, be subject to a recurring penalty payment, with a view to ensuring compliance. Member States shall also ensure that rightholders are in a position to apply for an injunction against intermediaries whose services are used by a third party to infringe an intellectual property right, without prejudice to Article 8(3) of Directive 2001/29/EC.

133 An interpretation of the third sentence of Article 11 of Directive 2004/48 whereby the obligation that it imposes on the Member States would entail no more than granting intellectual-property rightholders the right to obtain, against providers of online services, injunctions aimed at bringing to an end infringements of their rights, would narrow the scope of the obligation set out in Article 18 of Directive 2000/31, which would be contrary to the rule laid down in Article 2(3) of Directive 2004/48, according to which Directive 2004/48 is not to affect Directive 2000/31.

134 Finally, a restrictive interpretation of the third sentence of Article 11 of Directive 2004/48 cannot be reconciled with recital 24 in the preamble to the directive, which states that, depending on the particular case, and if justified by the circumstances, measures aimed at preventing further infringements of intellectual property rights must be provided for.

As you can see the CJEU does not explicitly say that ‘yes, the injunctions are to be provided regardless of any liability of its own’. On the other hand, it says that restrictive interpretation of the third sentence of Article 11 should be rejected. It still does not say however much clearly what is the answer to the formulated question, but lets see further:

135 As is clear from recital 23 to Directive 2004/48, the rules for the operation of the injunctions for which the Member States must provide under the third sentence of Article 11 of the directive, such as those relating to the conditions to be met and to the procedure to be followed, are a matter for national law. [this was later confirmed also in Scarlet Extended and Sabam]

136 Those rules of national law must, however, be designed in such a way that the objective pursued by the directive may be achieved (see, inter alia, in relation to the principle of effectiveness, Joined Cases C‑430/93 and C‑431/93 Van Schijndel and van Veen [1995] ECR I-4705, paragraph 17; Joined Cases C‑222/05 to C‑225/05 van der Weerd and Others [2007] ECR I-4233, paragraph 28, and Joined Cases C‑145/08 and C‑149/08 Club Hotel Loutraki and Others [2010] ECR I‑0000, paragraph 74). In that regard, it should be borne in mind that, under Article 3(2) of Directive 2004/48, the measures concerned must be effective and dissuasive.

- Bigger circle represents the entire, maximal, scope of intermediary liability defined by art. 8(3) InfoSoc, art. 11 and art. 3 IPRED, i.e. a) fair, b) equitable, c) not unnecessarily complicated, d) not costly, e) do not entail unreasonable time-limits or unwarranted delays, f) effective, g) proportionate, h) dissuasive, i) do not create barriers to legitimate trade, j) are not abusive;

- Smaller circle represents the effective and dissuasive intermediary liability as a minimal threshold required by paragraph 136 of L’Oreal v. eBay (above).

- The blue area is the difference between required minimum and possible maximum of intermediary liability.

- is there at all any such a blue area?

- or are minimal and maximal scope actually indentical?

Shall the CJEU say that certain website blocking injunction is

a) outside of the biggest circle – it means that such injunction is against the Union law;

b) in the blue area – it means that such injunction is compliant with the Union law, but does not have to be provided in each member state;

c) in the green area – it means that such injunction is compliant with the Union law and has to be provided in each member state;

What is your take on this? How do you read these lines?

Update. My friend Lassi Jyrkkiö pointed out to me an interesting excerpt of the General Advocate opinion in Google France C-236/08:

48. The goal of trade mark proprietors is to extend the scope of trade mark protection to cover actions by a party that may contribute to a trade mark infringement by a third party. This is usually known in the United States as ‘contributory infringement’, (19) but to my knowledge such an approach is foreign to trade mark protection in Europe, where the matter is normally addressed through the laws on liability. (20)

FN 19 – Contributory liability for trade mark infringement has developed as a judicial gloss on the Lanham Act of 1946, which governs trade mark disputes in the United States, although not expressly provided in the act. See 15 U.S.C. § 1051 et seq.; Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 US 844, 853‑55 (1982). Since Ives, contributory infringement suits in the United States have been brought under the Lanham Act, rather than under tort law. See, for example, Optimum Technologies, Inc. v. Henkel Consumer Adhesives, Inc., 496 F.3d 1231, 1245 (11th Cir. 2007); Rolex Watch USA v. Meece, 158 F.3d 816 (5th Cir. 1998); Hard Rock Cafe Licensing Corp. v. Concessions Services, Inc., 955 F.2d 1143 (7th Cir. 1992). Even in the United States, however, contributory liability for trade mark infringement is seen as closely related to general liability law. When applying the United States Supreme Court’s language in Ives, courts ‘have treated trade mark infringement as a species of tort and have turned to the common law to guide [their] inquiry into the appropriate boundaries of liability’ (Hard Rock Cafe, 955 F.2d at 1148). As a result, courts differentiate between contributory infringement and direct infringement and generally require proof of additional factors imported from tort law in the contributory liability context. See, for example, Optimum Technologies, 496 F.3d at 1245.

FN 20 – See, as regards France and the Benelux countries, Pirlot de Corbion, S., ‘Référencement et droit des marques: quand les mots clés suscitent toutes les convoitises’, Google et les nouveaux services en ligne, dir. A. Strowel and J.‑P. Triaille, Larcier, 2009, p. 143.